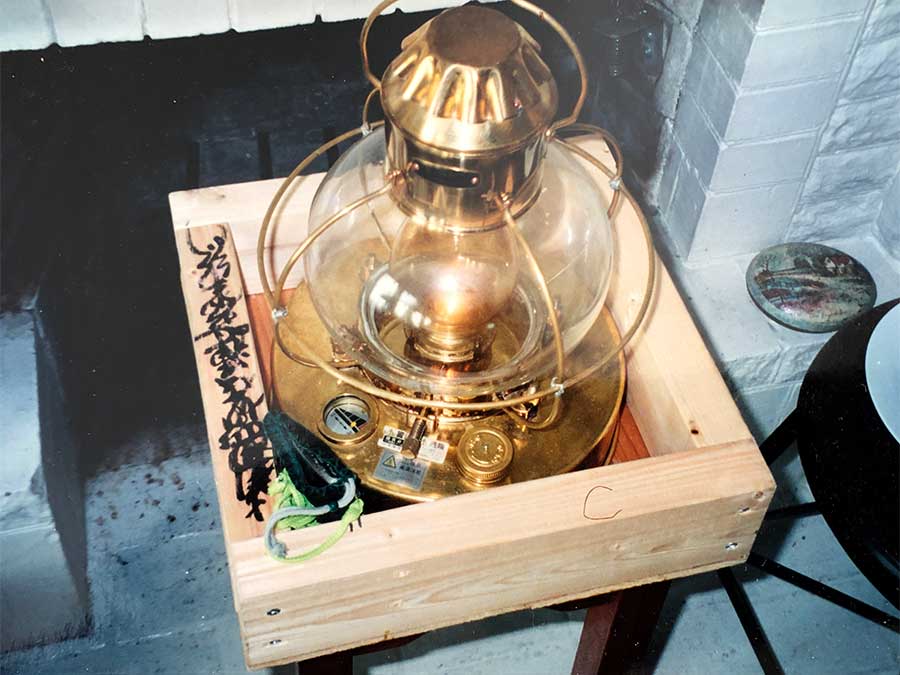

The Hiroshima Flame rests overnight in a home outside Washington, D.C., 2002.

As my new book, Inherited Silence, moves toward publication in July 2022, I’ve been thinking about its underlying themes—the history we have not reckoned with and the urgency of doing so. The story that follows came up in a writing group as I sat on zoom in the circle of women whose energy helped birth the book. The words that came prepared me for the death of my sister shortly after, and the violence about to explode in Ukraine—the sadness and fear of what might follow. My sister and I were children at the time of Hiroshima and raised on cold war fears. We didn’t realize then how nuclear weapons would open the way to dangerous nuclear power plants like Chernobyl and Fukushima or how our fears had been shaped by earlier events. We lived long lives with those fears—mostly in silence. She with three wonderful children and seven grandchildren. I with no offspring but an active life as a peacewalker.

I feel the grandmother in me as my sister grows weaker in hospice, her children in the pain I remember so well from our own mother’s passing. The house we’ve owned together all these years since our parents died, on land our ancestors grabbed up in a time of genocide still not acknowledged or atoned for. It’s now on the market again after 165 years. I am the oldest sister, who never settled into a relationship welcoming to children. I am the aunt and great aunt of my sister’s children and grandchildren. I am the family historian, the land-loving one, the one who wants to heal our legacy. I wear my rosy stone “heart” earrings every day now, to remind myself that love is of the essence, the only path through these troubling times. I am suddenly in the grandmother seat. What IS this role?

It hasn’t happened often, but I felt the grandmother energy in me on the streets of Manhattan in spring 2002, just months after the fall of the twin towers. That event had been a wake up call for many of us who knew things could get much worse in our country and the world if we were not able to face and transform the terrible pain of our history with love.

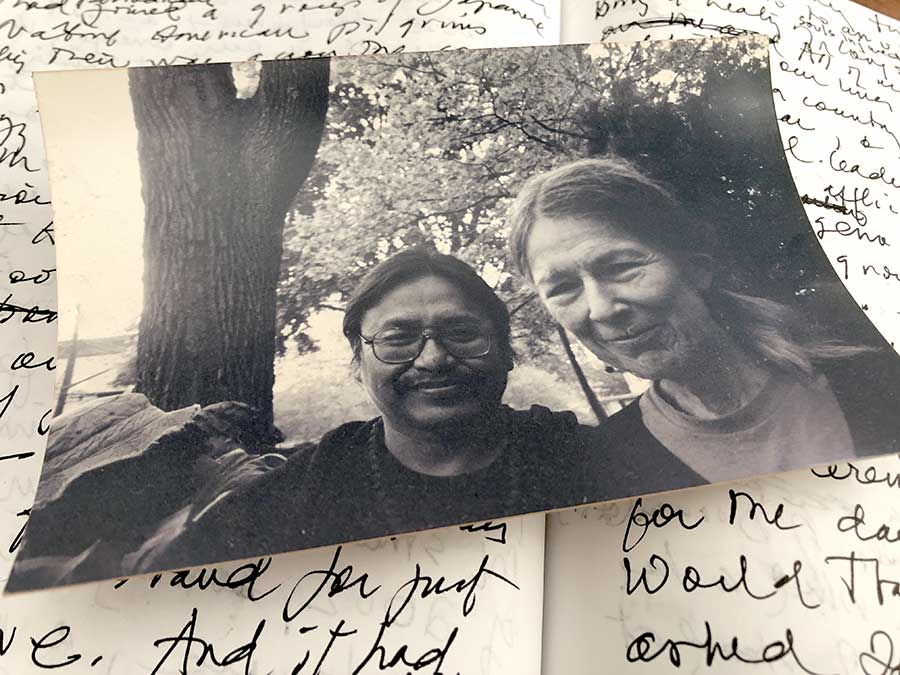

On 2002 Flamewalk: Durwin White Lightning and Louise Dunlap. Photo by John Toren.

That winter I had joined a group of Japanese and Native American pilgrims making their way across the country on foot from the west coast. We were carrying a kerosene lantern lit with a flame from the embers of Hiroshima that had been saved for generations on a family altar. The family’s bookstore had been incinerated in the blast, and they’d brought coals from the wreckage to burn on their Buddhist altar in memory. At first that flame fed feelings of loss, anger and revenge. But over decades of prayer by family grandmothers it had come to stand for love. After 9/11, the flame had been made available to legendary Buddhist nun, Jun san, for this momentous journey from one ground zero to another—to bring a healing of injured souls and the longstanding world karma that had led over and over to such atrocities.

All of us on this journey—taking turns carrying the flame in its unusual handmade carrying case—felt this healing in our personal lives as we traveled through a country wracked with grief, fear, and anger. In the evenings and at rest stops we talked it through, heart to heart with each other as we went along. Helping the flame to heal our own lives.

Spiritual leaders from tribes afflicted by our nation’s genocidal actions on their sacred homelands had helped to plan this journey. Somewhere in New Jersey as we approached our destination, one of them asked me to participate in a ceremony being planned for the day we would reach the World Trade Center site. He asked if I would be the grandmother in this ceremony. None of my protestations that I was only 63, a descendant of settlers, and not really a grandmother carried any weight. Durwin White Lightning of the Standing Rock Reservation just looked at me and told me that in his culture I WAS a grandmother and they needed me to do this. Of course, I said yes. I felt honored but also very humble.

Somewhere I still have notes on that ceremony. I know we approached through streets crowded with the signs and memorials citizens all over the city had put out for their lost loved ones. Amongst the shocked faces of thousands of visitors to the terrible wreckage, we passed through the crowded public sites—chanting and prayerful—until we reached a designated quiet intersection where we had permission to set up an altar. Our structure rose out of the rubble, covered with blooming flowers and lovingly folded peace cranes, providing a place for the flame we had carried and for heartfelt prayers in all the languages represented in our group.

Central to it all, the Wiping the Tears ceremony put together by Durwin White Lightning (Dakota) and Tom Dostou (Innu) featured a huge medicine wheel where I was to stand at one pole, with one walker each at the three others. One of them was Wataru, young son of sculptor Tom Matsuda, who had joined us when we reached the coast. After a prayer Durwin had received from his Standing Rock ancestors, I was to offer a grandmother’s prayer for healing and to sing a song. I don’t remember the words of my prayer—it just rose up from the site itself and the consciousness I’d reached on the Flamewalk. But I do remember singing Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh’s song, “No Coming, No Going,” which felt like it could help release all those injured souls. I belted it out the best I could, knowing my feeling would cover for my lack of a singing voice.

No coming, no going

No after, no before.

I hold you close to me,

I release you to be so free

Because I am in you

And you are in me.

Because I am in you

And you are in me.

In the confusion and strangeness of that day, I felt the energy of the love I’m talking about—the love of the grandmother—felt it envelop myself, the friends I had come to know on the walk, and all their healing stories. I hoped it could also reach the many, many souls affected by the massive deaths at the original Ground Zero, at Chernobyl in Ukraine, at this site we faced now, and in the centuries of historic violence that stretched back before our lifetimes.

So beautiful, Louise. Thank you for your deep witness. Spirit is using you well.

Thank, you, Grandmother Louise. 13th-Century Zen Master Dogen encouraged every person, even young male monks, to nurture “Grandmother mind, the mind of great compassion.”

Wonderful to read this story! I will share it with our daughter, who has few memories of Durwin.

Thanks,

– Dharmika