Since the 1960s, I’d been involved in all kinds of activism — showing up in downtown Boston whenever a new war started, picket lines at workplace strikes and suburban homes of recalcitrant landlords, arrests in my senator’s office when he wouldn’t meet to talk about El Salvador, and ten years on my city’s unique Peace Commission. I’d written press releases and informational handouts about apartheid and supported students who were being racially profiled by campus police. I’d organized teach-ins and forums and even a study trip to Cuba when it was very difficult to get there.

But starting in 1990 when I traveled to Wounded Knee for a ceremony to “wipe away the tears” of that terrible history, I began to look for ways to be active that included healing. That’s when I found engaged Buddhism with Thich Nhat Hanh, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, and the small Japanese Buddhist order Nipponzan Myohoji with its organic connection to Indigenous ways of activism. Walking together through the injured landscape, chanting simple words from the Lotus Sutra with people deeply affected by the harm, stopping for ceremony in places of devastation, meeting with local communities and raising awareness of our hidden history—these now centered my activism. I walked long miles to call attention to climate change, to heal the history of enslavement, prisons, and the colonial legacy of Columbus. After 9/11, I helped carry a burning ember kept alive from Hiroshima across the country to the Manhattan site that was now being called “ground zero.” I wrote about walks, including dozens of articles in peace media that are not on the ‘net. And when I moved to California, I helped organize a powerful walk following the disaster at Fukushima—The Sacred Sites Peacewalk for a Nuclear-Free World. To learn about current peacewalks, contact Nipponzan Myohoji centers in New York, New England, the Southeast, and the Northwest or their ally, Footprints for Peace.

Vietnamese poet and Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh uses the term “interbeing” to express the principle that animates our world. We are not separate individuals but humans connected with each other and with all the other beings, elements, and forces in what we have called “nature.” We are interdependent with everything from the asylum-seeker with her children to the ice of the Himalayas. Indigenous teachings are very similar. How do we live in harmony with interbeing when our culture is rooted in a more individualistic and competitive paradigm?

One way for me is actively being with the earth, learning to listen to what the land wants, to act in reciprocity without seeking control. In recent years I’ve worked directly with rural family land learning about how the First People cared for it and making connections that can truly restore and repair. Gardening on this land and in the city are one way to practice interbeing.

It helps to live in an urban co-housing community with at least three generations of people and many plants and animals in our living network. I also engage with Indigenous groups in my city—a seven generations-oriented urban farm and an innovative land trust led by Indigenous women from this very location. I even pay a tax to them for the benefit of living on their un-ceded land. I attend water ceremonies with local members of The Indigenous Women’s Climate Treaty. In keeping with my commitment to Thich Nhat Hanh’s Order of Interbeing, and the fourteen precepts that anchor it, I meditate with several Buddhist groups, sometimes on line. One that I helped found is dedicated to awareness and healing to help white practitioners better contribute to Beloved Community in these divisive times. I’m in study and discussion groups that seek to build new consciousness and, after years of teaching yoga, I now practice Wild Goose Qigong and Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement.

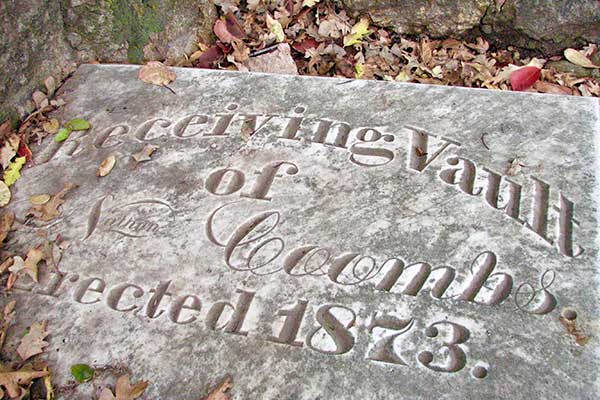

“Colonizer mind” is the term I found myself using as I wrote about my settler ancestors and the mentality that shaped colonization in this country and remains with us today. We haven’t outgrown “manifest destiny,” the 19th century idea of a white American superiority, supposedly destined to take over the world and continuing to cause great harm. As Deena Metzger has so eloquently said, “climate change arises from the same colonial mind that enacted genocide on the Native people of this country.” Many white Americans are unaware that this mindset still lives in us, that we are shaped by the entitlement of our history as well as its trauma and silences. Every day I catch myself in remnants of it.

When my book is done, I want to create a curriculum for awareness, grieving, and healing colonizer mind so we can move into the future with greater integrity. Meanwhile, I’m active with my Buddhist community working to shift consciousness about systemic racism and its effects on us all. I began in Boston years ago and I rejoice, now, to see many other American Buddhists taking up this challenge, including my own community.